Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) is a condition of newborn brain sickness that can be caused by impaired oxygenation of a baby during labour and delivery. Unfortunately, this can lead to brain injury and profound physical and cognitive disability. Some babies will end up suffering from Cerebral Palsy (which involves motor dysfunction and cognitive challenges) or with neurodevelopmental problems (that might cause learning disabilities and behavioural issues).

HIE is caused by an impairment of oxygenation to the brain. This can be related to issues with the placenta and issues with the umbilical cord. Your fetus is supplied with oxygenated blood through the umbilical cord. The umbilical cord is attached to the placenta. Any condition that impairs the flow of blood to the placenta (for example, uterine contractions) or to the umbilical cord (like a compression of the cord, or nuchal cord – when a baby has the umbilical cord around the neck) has the potential to impair oxygenation to the fetus.

Learn more about electronic fetal heart monitoring

- What does the EFM do?

- How does the EFM work?

- Explaining EFM Data

- Patterns of fetal heart rates

- EFM classification

- Learn from an expert

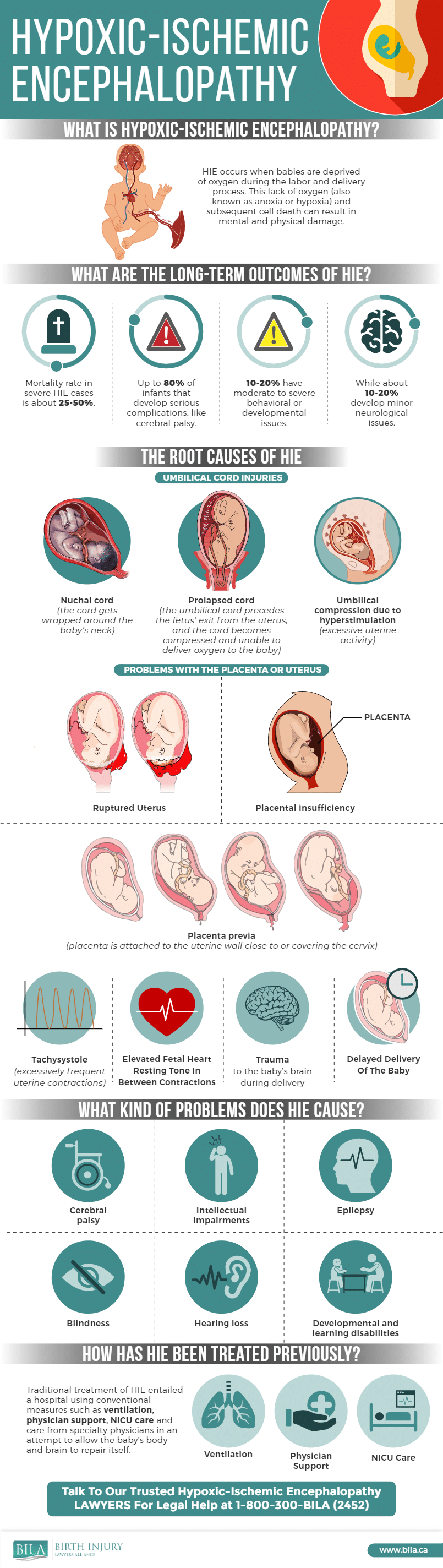

Here is an infographic describing HIE:

A healthy and well-grown fetus has considerable capacity to tolerate intermittent interruptions in oxygenation, particularly if any episodes of impaired oxygenation are separated by adequate rest and recovery. This capacity to tolerate the normal stresses of labour is often referred to as “fetal reserve”. A fetal reserve is not, however, unlimited. If episodes of impaired oxygenation are allowed to go on too long or are too severe, the fetal reserve can be depleted and, eventually, exhausted. Some babies may come into labour with less fetal reserve, particularly babies that might have been growth restricted (small babies) during pregnancy.

During labour and delivery, your baby’s well-being is assessed by nurses and doctors by monitoring the baby’s heart rate. There are features of the fetal heart rate, when interpreted properly, that can suggest a possible problem with fetal oxygenation.

The most important tool that doctors and nurses use to measure your baby’s oxygenation during labour and delivery is the Electronic Fetal Heart Monitor (EFM).

What does the EFM do?

The Electronic Fetal Monitor provides a continuous tracing of the fetal heart rate (“FHR”). At the same time the same monitor provides a continuous tracing of the uterine contractions. The nurses and obstetricians use this continuing tracing to see if the pattern reflects a fetus that is well-oxygenated or a fetus that my be under a degree of stress due to impaired oxygenation.

There are certain FHR patterns that are considered “normal”, indicating that one can be reassured that the fetus is coping with the stress of labour and that continuing with normal labour towards an anticipated vaginal birth is appropriate.

On the other hand, there are certain FHR patterns that one cannot be reassured about and that may require a change to the approach to managing the labour in order to protect the health of your baby. These patterns are called either “atypical” or “abnormal”. The FHR patterns must be interpreted in the context of the uterine activity, the stage of labour and the progress of labour.

The data on the EFM is one of the very crucial factors in determining whether injury occurred during labour and delivery and whether the standard of care required some other approach. BILA lawyers have spent a considerable amount of time studying the issues concerned with FHR patterns and the impact the EFM data has on proving liability.

How does the EFM work?

The EFM monitor has two devices that detect pressure called transducers. The transducers are placed on the mother’s abdomen and held in place with straps. From time to time it may be necessary for the nurses to adjust or move the transducers in order to achieve an adequate signal to produce a clear and continuous heart rate tracing on the recording strip.

The EFM has a screen or monitor that shows the fetal heart rate. The EFM also produces a printed strip of paper that is covered in grids showing time segments and heart rate. Data from the EFM monitor is plotted on the strips and looks like two wavy or spiky lines A properly trained professional can tell a great deal about the wellbeing of your baby during labour by looking at the lines on the EFM strips.

The top line of the EFM strip represents the fetal heart rate. The line spikes up (peaks) or dips down to reflect changes in your baby’s heart rate.

The bottom line of the strip shows the mother’s uterine contractions. The line spikes up (peaks) when you are having a contraction.

When the FHR pattern and uterine contraction pattern are looked at in together, properly trained nurses and doctors can learn a great deal about the well-being of your baby.

EFM monitors also produce sounds that are related to the fetal heart rate. The machines also have alarms that are supposed to sound when the fetal heart rate gets too fast or too slow.

Understanding EFM Data

It is important that the nurse and physicians caring for mother and fetus are properly trained in the use and interpretation of EFM data. There are a number of different factors that the EFM monitor will record that are critical to evaluating your baby’s health and well-being.

Contractions: One of the transducers measures the pressure produced when mom has contractions during labour. The EFM will detect the duration of the contractions (how long they last) and the frequency of the contractions (looking for a normal pattern of contractions occurring every 2 to 3 minutes, and not more often). The nurses or doctors monitoring the labour will assess the intensity of the contractions by palpating (feeling) the mother’s belly. They are also required to ensure that the uterus relaxes between contractions.

As stated above, the frequency of contractions should be about two to three minutes apart. When contractions come more frequently than one every two minutes it is called tachysystole. The risk of tachysystole increases when your physicians use certain drugs like oxytocin to try to induce or augment your labour. Contractions that last for a duration longer than 90 seconds are called hypertonic or tetanic contractions.

The problem with contractions that occur too frequently or that last too long is that they can contribute to impaired oxygenation of the baby. These uterine contraction patterns extend the time of stress on the fetus, increasing the risk of diminishing fetal reserve. Concerning fetal responses to these kinds of uterine contractions may be seen as changes in the pattern of the FHR.

Fetal Heart Rate Patterns

The EFM tracks a great deal of information that the obstetrical team must consider and use in making a determination about whether your baby is doing well during the labour (reassuring patterns) or if your baby is struggling (non-reassuring patterns).

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada has established guidelines defining the important data collected by the EFM. Unfortunately, some of these guidelines fail to provide adequate guidance on how to respond to some FHR patterns in the context of all the clinical circumstances. BILA lawyers have a familiarity with the current guidelines and, importantly, an understanding of the shortcomings.

Baseline: The baseline is, essentially, the average of how fast the baby’s heart is beating over a period of 10 minutes in beats per minute. When figuring out the average baseline, the nurse or doctor will exclude accelerations (spikes in your baby’s heart rate) and decelerations (dips in your baby’s heart rate) to come up with a baseline rate. The normal baseline for a healthy fetus is between 110 to 160 beats per minute.

If you baby’s heart rate goes above 160 beats per minute for extended periods of time (more than 10 minutes) this is a condition known as tachycardia. Tachycardia can be a sign of fetal distress.

When the heart rate drops below 110 beats per minute this is called bradycardia. Bradycardia is concerning and is also a sign of fetal distress. It usually means the baby is not getting enough oxygen.

Variability: Variability refers to the oscillation of the FHR above the baseline and dips below the baseline. A healthy baby’s heart rate usually fluctuates over time so it is normal and reassuring to see the variation in the heart rate over time.

If the oscillation in the heart rate is greater than 25 beats per minute the variability is classified as “marked”.

The variability that ranges between 6-25 beats per minute is classified as “moderate”.

Variation of less than 5 beats per minute is classified as “minimal”.

When the baby’s heart rate is traced essentially as a flat line the variability is classified as “absent”.

A healthy fetus will normally produce a heart rate with moderate variability. If FHR variability is minimal it can be due to a number of factors. Sometimes medication administered to the mother can reduce variability. Fetal sleep can be a cause as well. Finally, minimal variability can be caused by impaired fetal oxygenation and, therefore, as a cause for concern. Absent variability and marked variability are both non-reassuring.

The obstetrical care providers monitoring your labour will need to consider all the clinical circumstances and medical evidence to determine whether reduced variability is something that is normal and not of any concern or whether the reduced variability is a non-reassuring sign of potential fetal distress.

Accelerations: Sometimes the EFM monitor will show abrupt spikes in the heart rate. An abrupt increase in the heart rate of more than 15 beats per minute is referred to as an acceleration.

Accelerations are often normal and a reassuring sign that your baby is doing well. Having said that, accelerations occurring in the context of other atypical or abnormal FHR patterns can not be considered reassuring.

Decelerations: A dip in the heart rate below the baseline is referred to as a deceleration. There are different kinds of decelerations, each with slightly different significance for assessing fetal well-being. In addition to the various patterns and timing of decelerations, the depth and duration of a deceleration is clinically significant. Decelerations of longer duration and deeper depth are more concerning.

Early decelerations are a gradual decrease in the fetal heart rate that typically mirrors the mother’s contractions. This type of decrease in FHR is thought to be caused by head compression from a contraction. While many obstetrical texts and journal articles consider early decelerations to be normal and benign, there is more recent literature suggesting that no deceleration is entirely benign. As well, there is reason to believe that head compression has the potential to be harmful to the fetus when excessive or prolonged.

Variable decelerations are an abrupt drop in the fetal heart rate of more than 15 beats per minute lasting anywhere from 15 seconds to two minutes. Variable decelerations are commonly seen during labour and are thought to be caused by umbilical cord compression.

Variable decelerations are categorized as either uncomplicated or complicated.

Uncomplicated variable decelerations show an initial spike (acceleration) then a dip (deceleration) followed by another spike (acceleration) before the heart rate returns to the normal baseline. Uncomplicated variable decelerations that occur repetitively may be a sign of fetal intolerance to labour and intermittent decreased fetal oxygenation. The frequency, depth, and duration of these decelerations are important for determining the degree of distress being experienced by the fetus.

Complicated variable decelerations may have loss of variability in the baseline, maybe a deceleration in two phases, or maybe a deceleration that takes a long time to return to the baseline. Complicated variable decelerations are concerning and can be a sign of fetal distress.

A late deceleration is one where the bottom of the deceleration occurs after the peak (or tip) of the contraction tracing. Late decelerations are generally accepted by medical professionals to reflect some degree of hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) in the fetus.

Prolonged decelerations are decelerations that last for more than 2 minutes. These decelerations are concerning and require immediate clinical action from the obstetrical team.

EFM Classification

When your nurse or doctor looks at the EFM strip they have to consider all of the circumstances and all of the data on the monitor in order to classify the tracing.

It used to be that EFM strips were categorized as either reassuring (the information on the monitor showed that the baby was doing well) or non-reassuring (the information on the monitor suggests the baby may not be doing well). Unfortunately, this easy to understand classification system has been abandoned by the medical profession.

In recent years the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada have created new guidelines to categorize EFM strips as normal, atypical, or abnormal.

Normal EFM strips are considered to represent a well-oxygenated fetus and are generally what was once referred to as a reassuring tracing. In other words, the baby is likely to be happy and healthy.

Abnormal tracings contain data that strongly suggest that there are problems with fetal oxygenation and that the baby may be at risk of injury. Abnormal tracings usually require immediate action either to try to address the cause of the abnormal tracing or to expedite delivery of the baby by C-section or operative vaginal delivery.

Unfortunately, most EFM tracings fall into the atypical category. This category of tracing is poorly defined and consists of an FRH pattern that is neither normal nor abnormal. These types of tracings suggest that there may or may not be a problem fetal well-being and the baby may or may not require expedited delivery. The appropriate response to an atypical tracing depends on a consideration of the entire clinical context in which it occurs and is usually the subject of much debate in birth injury malpractice claims.

Expert Evidence

One of the first things that your birth injury malpractice lawyers will do will be to hire an obstetrical expert to assess the fetal heart monitor tracings. That expert will be asked to determine whether there was any evidence of fetal distress and whether the obstetrical team responded appropriately to the available data.

Experienced birth injury malpractice lawyers have some degree of skill in understanding and interpreting EFM tracings to determine whether there are potential grounds for concern and whether it is appropriate for further investigation by hiring a medical expert.

See Also: Improper Fetal Monitoring

- Long Term Effects of a Nuchal Cord - May 6, 2022

- Greatest Risks for Cerebral Palsy Occur Prior to Birth - August 28, 2020

- Alberta to Begin Screening Newborns for Four New Conditions - September 27, 2019